Our Story

Written by Mike Allen for The Roanoke Times

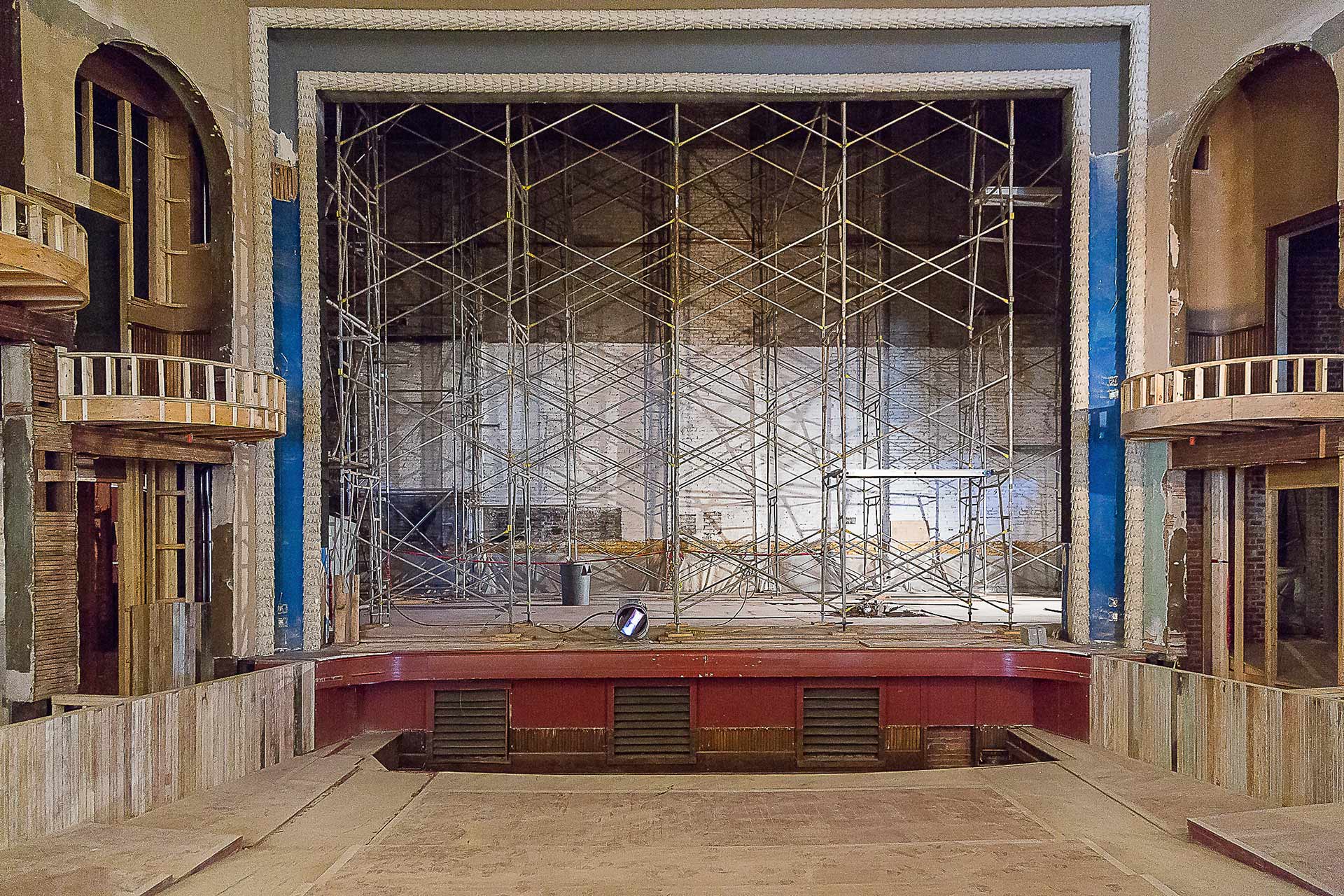

The old stage had to go.

Workers inside the Historic Masonic Theatre on Main Street in Clifton Forge pried up dry-rotted boards. At least 10 feet above them, pallets dangled from new rigging. The boxes on those pallets contained the new stage curtains, held in suspense until crews finished the unplanned replacement of the stage floor. Renovations tend to come with surprises. This one, though inconvenient, wasn’t going to keep the 110-year-old theater from being ready for its July 1 grand reopening.

Seven years ago, a determined group of residents set up the Masonic Theatre Preservation Foundation to restore the crumbling theater to life. This month, the $6.5 million construction project is nearly done. “It’s not an end. It’s just a beginning,” said John Hillert, the retiree from the insurance industry who started the push to save the theater. The grand reopening [included] big-band music by the Sway Katz and Americana rock from the Scott Miller Trio, a screening of “The Wizard of Oz,” and tours of the theater, which promoters dub an “architectural treasure.”

“It’s a remarkable project,” said theater executive director Jeff Stern. “You can feel the love, the desire from the community, in the building when you walk into it. It’s a meaningful part of Clifton Forge and the history of this region.”

The reopening of the theater launches the most ambitious piece of a concerted effort to recast the 3,884-population town, once home to a major maintenance shop for the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway, as a hub for creativity and a picturesque destination for tourists. The theater is intended to serve as the crowning jewel of a small downtown with shops, restaurants and galleries all in walking distance. “We’re very proud of what’s happening up here,” said Clifton Forge town manager Darlene Burcham.

A process of rediscovery

Other surprises that arose after the renovation began in April 2015 provided cause for celebration rather than concern. When contractors removed plaster on the four-story building’s west side, they uncovered a brick wall decorated with a sign painted in the 1800s advertising a shoe business.

Much of the funding for the construction comes from federal and state tax credits intended to encourage the rehabilitation and preservation of historic buildings. Theater officials got permission from state and federal authorities to preserve the antique Roberts & Tinsley Shoes mural.

Stern said the theater holds striking revelations from the past on every floor. According to a history compiled by the foundation, Lynchburg firm Frye & Chesterman laid the cornerstone for the theater in 1905. Low Moor Masonic Lodge 166 commissioned the building to serve not just as the fraternity lodge, but as an opera house that would benefit the region — much the way the members of the Historic Masonic Theatre Foundation view their mission now. “They really envision this as a community center,” Stern said.

The Mason Hall and Opera House opened in September 1906, the same year Clifton Forge was chartered. Its stage hosted such notables as politician William Jennings Bryan, Hollywood stars Lash LaRue, Gene Autry, Burl Ives and Hopalong Cassidy, and jazz legends Count Basie Orchestra.

Since its beginnings, the theater also served as a movie house, and a meeting place. Nostalgia for the theater runs deep in the region. Hillert said that when he conducted interviews to determine whether the community would support a renovation, he heard from residents who met their spouses there — if one’s parents didn’t approve of a match, the theater was a place a young couple could still meet.

Hillert, 65, and his wife, Gayle, 66, moved to Clifton Forge 10 years ago. Gayle Hillert, who grew up in Virginia, had advocated for her home state as a good place to retire.

Her husband spent time in the town while she was still working at her employer’s Switzerland office. As she recalled, he sent an email after seeing a show in the run-down theater. “This old theater in Clifton Forge is unbelievable, but it needs to be saved,” he wrote. John Hillert feels that he gets too much credit for the theater’s restoration. “I was a new voice saying this is something that we as a community needed to do,” he said. He led an effort to study whether the restoration was feasible, and whether the community would get behind it. The Hillerts found an ally in Clifton Forge attorney Meade Snyder, whom they credit with navigating the incredibly complex process that made it possible to use tax credits to help fund the construction.

John Hillert was the first president of the Masonic Theatre Preservation Foundation. He stepped down to become president of Masonic Theatre Inc., a for-profit company created to allow the use of tax credits. Snyder took over as president of the foundation. Gayle Hillert, in addition to being foundation secretary, has served on the Clifton Forge town council for six years. Three years ago, her fellow council members appointed her as vice mayor.

It took five years to secure the funding, John Hillert said. Funding from big donors wasn’t feasible. “There was not a wealth of wealth in the area,” he said.

Theater officials chose not to start construction until all the money was in hand. The Alleghany Foundation, a Covington-based nonprofit with a mission to improve quality of life in the Alleghany Highlands, awarded $2.4 million toward the theater’s construction.

Space for diversity

As redesigned, the structure holds four venues that can be used for performances or art exhibits — but not just for that. “You name it and we’ll do it,” Stern said. “Zoning hearings and meetings, weddings … That’s not just a way to make money. That’s a mission-based piece for us.” The building is meant to be a place for community activities as well as a performance hall. The main theater in the building’s heart seats 545, and can host movie screenings and stage shows. The heating and cooling systems have been installed under the seats to preserve the historic character and minimize the impact on acoustics. The main theater’s balcony contains a relic of the Jim Crow era. When racial segregation was enforced, black patrons had to ascend the fire escape to the second floor, pay admission at a separate box office, and, from there, climb another set of stairs to the balcony. Though that second set of stairs is now blocked, the space will be used to house a permanent exhibition acknowledging that part of the theater’s history, Stern said.

Despite that ugly aspect of the theater’s past, theater officials found that blacks in the community also thought of the theater as their theater. “It was a place that welcomed everybody,” Gayle Hillert said. “We have a very diverse audience.” Beneath the auditorium, the foundation has installed a basement cafe that opens into a lounge directly under the theater seats, with windows that look out onto Smith Creek, which runs along the building’s east side. Dubbed the Underground, the venue could host poetry readings and performances by local bands. “These are spaces that are just made for local talent,” Stern said.

Above the main theater, the meeting hall where the Freemasons once held their secretive gatherings has been repurposed as another venue for hosting events. The hall has an adjoining kitchen for catering. The ceiling sports examples of the molded plaster decorations that can be found throughout the building, of the sort seen in Roanoke in the recently closed Wells Fargo bank building at Campbell Avenue and Jefferson Street.

A newer structure outside the building provides the organization with its fourth venue for programming.

In 2012, Virginia Tech architecture students constructed a steel-and-wood amphitheater on the site of a tire warehouse that once stood next to the Masonic Theatre. The amphitheater has a sleek, space-age look, more in line with the Taubman Museum of Art than something the Freemasons would build. Essentially a class project, the amphitheater was made part of the overall theater complex. A new walkway and stair over Smith Creek helps link the two.

Turning the engine

With construction winding down, organizers are shifting their focus to operations. Four months ago, the foundation hired Stern as the theater’s first executive director.

A transplant like the Hillerts, the 49-year-old previously worked as director of arts centers in Loudon County and Hampton. Since he started, Stern has made it his mission to get to know his adopted community. “We are by definition a regional facility,” he said. “My backyard is all of Alleghany County.” The theater will start with an annual operating budget of $225,000.

Officials are quick to point out that the Historic Masonic Theatre isn’t the only act in town. The Clifton Forge School of the Arts stands just across the street from the amphitheater. The Alleghany Arts and Crafts Center is a short walk from the theater’s front door. The C&O Railway Heritage Center is also close by. If Clifton Forge comes to be seen as a regional arts destination, “that’s when the economic engine really starts to turn,” Stern said.

The proximity of Douthat State Park helps to draw visitors, Burcham said. The town can also boast of an amenity Roanoke doesn’t yet have: an Amtrak passenger rail station.

In recent years, bed and breakfasts have opened. A popular downtown restaurant, Jack Mason’s Tavern, has plans to start a brewery. “I think you can never have too much of this type of thing,” said Shauna Donovan, co-owner of The Moody Carpenter, an antique shop beside the theater. With the theater in place, she could picture Clifton Forge turning into a town like Floyd. “I’d like to see that happen here.” John Hillert believes the town needs to establish an arts district, to help market the town’s full range of offerings. “We have a whole bunch of pieces that work side by side,” he said. “What we need to come up with is a way to link hands, link arms and bring the most people in that we can to come see what we have in Clifton Forge.”